I randomly stumbled across the Historical Movie Costume tumblr and was scrolling through it when I came across one of the most persistent myths in historical costuming: Buttons aren’t period for [insert period here].

It’s not that I just want to shit all over this tumblr blogger, who I’m sure is a lovely, well-meaning person, but I can’t let something like this go unaddressed.

I first encountered this myth when I was a wee Sarah who had just discovered the “historical fashion” section in the 1973 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. I was drawn in by the full-color spread showing women’s clothing from antiquity to the 20th century and dragged the massive tome over to a trusted adult who shall remain nameless to show her the illustration of a medieval gown I had fallen in love with. And I can’t remember how the conversation went, but at some point, she said, “Those buttons on the dress were just decorative. They didn’t have functional buttons until the 19th century.”

I have to admit, even at 12-years-old, this smelled of bullshit. Why the hell bother with sewing a bajillion little buttons that had no purpose? Pretty sure the response to that was to shrug and say, “Because, fashion is weird.” A few years later, when I joined the SCA as a young teen, I came up against this myth again: “Buttons aren’t period for the middle ages.”

Still smelled of bullshit, but since this was still a decade before major institutions began putting their collections online, and still several years before I would go to the Museum of London and come face-to-sleeve with a fragment of a medieval gown with very definite buttons and buttonholes, I had no grounds to object.

I truly have no idea where this myth came from, but apparently, it doesn’t seem in danger of dying out.

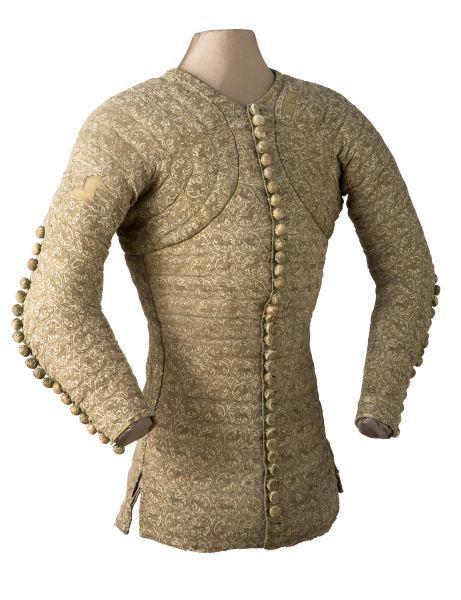

If you look at button history, we certainly have examples of buttoned garments in both art and extant clothing dating at least to the 14th century in Europe and earlier in the Middle East. And yet, it’s just accepted that our ancestors, who built massive aqueducts, and flush toilets, and could calculate the circumference of the earth to within 17.5 km using only their brainmeats … that somehow button technology eluded them.

< sarcasm > Seems legit. < /sarcasm >

So, let’s recap.

Buttons…

aren’t…

period…

for…

18th-century

women’s…

clothing.

I love you ladies!

Just had to say.

So. Much. Evidence. Makes you wonder how she came to this conclusion…

God, who knows? I took a costume history class, from a professor I respected, as part of my under grad degree and it was filed with bullshit myths like this one. You think I’m obnoxious now? You should have seen 24-year old Sarah raising her hand every ten minutes to correct the professor after yet another blatant inaccuracy that could be refuted by actually bothering to look at a portrait or extant piece of clothing was rattled off in class.

Pretty sure everyone hated me. Whatever. Don’t fuck up history, bitches. I will end you.

Standing Ovation!

You are my idol!

Why do those ‘uninformed’ professionals who should know better believe this? If you look and examine period clothes (I was lucky enough to do that with a man’s 18th century piece – gorgeous buttons & Silver lace at LACMA) Are professor caught up with their own reputation & ego…

But buttons are and have been functional. Just look at those gorgeous pieces at Musee Galliera, Les Arts Decoratifs, V&A, LACMA and the Met.

Argh false information makes me want to snark and throw popcorn at the source.

Love post. Up the button!

With this professor, I think it was more that she was teaching from the book (it was this textbook) and sort of dialing it in. This particular survey course was trying to cram 20,000 years of fashion history into a 10-week academic quarter, so there was a lot of skimming. And, like I said in another comment below, the vast majority of people in that class really didn’t want to talk about nuance. They just wanted soundbites.

Having taught from that same textbook myself, the whole thing is pre-packaged with a CD of PowerPoint presentations for every chapter, so you could literally put minimal effort into the curriculum — if you’re tapped to teach fashion history and you’re not a fashion historian, this is fabulous. If you’re like me, a pedantic clothing historian who is obsessed with historical accuracy, the whole thing is an exercise in contradicting the textbook practically every other page.

I’d feel somewhat cheated if the professor taught only from the textbook, but I’ve also had courses like that. I just made sure I never signed up for any other courses the prof taught.

But thanks for the information & response.

And remember the Romans used a form of large sophisticated safety pins to fasten their clothing.

Buttons were widely used in the Middle Ages. when Europe underwent a mini Ice Age and it became necessary to lap layers of fabric in order to provide more warmth.

Oh, and for goodness’ sake, remember mens’ 18th century waistcoats with their buttons!

I’m boggled by this purely because I’ve never come across this myth! Is this one of those weird American things?

Yeah, I’m like you. I didn’t know it was an issue.

I mean, we have eyes, no?

When I was a student in costume making (in France) I was taught that buttons first appeared in women’s clothes during the 18th century… so I didn’t know about those older ones (though I knew they were common in men’s clothes). So, not really an american myth :)

I really don’t know where the button myth got started, but I have a sneaking suspicion that it’s from one of those early-20th century costume historians like Herbert Norris or the Cunningtons that basically invented whatever suited their narratives about clothing and society, and who never cited their sources because they were the experts so why should they?

A lot of weird costume “history” can be traced back to those three.

What I’ve noticed is how many more buttons vintage patterns used than modern clothing. Maybe because they didnt have zips?

Hooray, a Post in Defense of Buttons! This is definitely one of those weird myths that refuses to die, I encountered it when we did a dressmaking demo at an 18thc site. “oh so you’re not using buttons because they were considered improper for women in the 18thc, right?” Um…sure. Those scandalous manly buttons, amirite?? (No.)

I do wonder if some of the confusion about closures pre-18th-century is because people hear blanket statements like, “most women’s dresses were fastened closed with pins” or “most women were sewn into their dresses,” so therefore, fasteners like buttons weren’t used. And if they weren’t used, it must be because they didn’t exist.

It follows a weird kind of logic, even though it’s demonstrably false.

Also, I think the vast majority of people just don’t bother to look at art that closely. So, even if they’ve been shown an 18th-century portrait of a woman, their brains edit a significant amount of the details because they don’t really matter overall. “Oh, it’s a picture of a woman in a fancy dress, ok, moving on…” Something as trivial as closures or seamlines doesn’t matter to the brain if there’s no reason to look for that information. Therefore, someone is half-listening in their costume history class and hears “Women were pinned into their gowns,” while being shown a picture of a woman in a weird-looking dress, and they’re like “Cool, so there were no buttons. Got it. Moving on.”

It’s one of those things that people love to hang onto, I think because it makes clothing of the past so weird and different omg, which is the impetus behind most historic house myths, as far as I can tell – they were really short! They slept fully sitting up! They were all dirty and gross all the time! Only prostitutes wore green! &c. &c. Buttons being completely unknown or thought to be offensive on women is really bizarre and memorable.

That said, I think it’d be fair to acknowledge that buttons weren’t an all-purpose closure. The myth is correct in that women’s gowns didn’t tend to just button up the front: the buttons appear on compère stomachers, redingotes, riding habits/traveling dress, and fanciful or semi-imaginary “Turkish costume”.

It reminds me a lot of what one of my graduate professors said with regards to teaching history to non-historians (ie. undergrads who just need to take a history course to satisfy a requirement): Most people do not want nuance. They do not want shades of gray. They want true or false, black or white, this or that.

In this case, the statement “buttons didn’t exist in 18th century women’s clothing” is false, because they totally did. But the nuance is that, like you said, they weren’t the most common method of closure on women’s clothing and tended to be adapted from menswear or from an exotic culture. You and I could totally write a giant paper on the historiography and social-sexual significance of buttons in 18th-century women’s clothing, WHICH, BTW, WOULD BE FUCKING EPIC, but 99% of the rest of the world be like, “Meh, who cares?”

I’d buy that paper!

I’d totally read that!!

Let’s do it!

I’m totally down! Let’s talk! IM me on fb, bb.

I love this post and you for writing it.

What myths did the Cunningtons establish?

Really, with the Cunningtons, it wasn’t so much myths, but the fact that they tended to disregard provenance as a matter of course and paint with really broad strokes that ignored a lot of actual historical source material.

I got wrapped up with them accidentally when I was studying the chemise a la reine at Platt Hall, which turns out was part of the original Cunnington collection of costume. The collection notes for the chemise amount to “purchased from vendor in Petticoat Lane in 1947.” Like, this is one of the rarest examples of 18th-century clothing, one of TWO that exist pre-1790, and that’s all they cared about documenting?

I ended up in this utterly fascinating conversation with Miles Lambert, the director of Platt Hall, which boiled down to the fact that all of the original Cunnington collection garments have “provenance” that amounts to the year the garment was purchased and a vague reference to a vendor. Apparently, the Cunningtons felt that the history/provenance of a garment was irrelevant — they were interested in some kind of early-20th-century historical imperative to wipe away the “irrelevant” things like who owned the dress, how it was worn, where, why, etc. and focus instead on the broader impact that clothes had on society across time. They apparently felt that understanding context of a garment in its original setting was less important than the broadest, zeitgeist-iest, “psychology” of dress when comparing it to modern fashion.

This leaves a lot of blanks in the historical record that were filled in with the broadest strokes possible. And since the vast majority of what we, as fashion historians, have to work with is heavily derived from the Cunningtons’ work, it means a lot of those blanks still exist, unaddressed and unquestioned, in contemporary research.

Edit: This is a pretty good overview of the problems with C.W. Cunnington’s methodology. And now I’m falling down the Cunnington rabbit hole again…

Now I’m with you. Have lot to say but can’t, cos on mobile.

Basically: Post Comment button disappears if I type more than 2 or 3 lines of text in response. Even if “viewing in Web page mode”. Annoying.

But yes. Cunningtons attitude to provenance bloody wack. Valid theory but still nightmare.

OK – Now I can reply in more detail. I understand WHERE his idea came from. I strongly disagree with the reductionist-to-types approach as I love provenance and background stories, but I can understand his thinking. Fortunately I’m not familiar with his theories, but more up to date with the general fashion overviews he put out, such as the 19th century fashion book with quotes from magazines etc. An important figure in early fashion history-history, but very problematic from a curatorial perspective, as are so many of the pioneers!

I do appreciate that he and Phillis were always so outspoken against the metal corset myth, as they were medical practioneers so they were more than qualified to say “these are for medical use, not fashion” – whereas Herbert Norris was clearly fapping himself silly over the idea of domineering husbands locking the naughty little Tudor wifey in her corset until she promised to submit and behave. (Vom)

At least they said metal corset myth as perpetuated by pervy Norris bullshit except for medical reasons.

basks in your salt

Not being an historical clothing aficionado I was looking at the Outlander season 3 outfit for Claire and thinking she would have stood out from the crowd with those front buttons. Obviously I was wrong. Glad to be informed. Though I really wish they had stuck with the Jessica Gutenburg dress with the back zipper from the book. Changes a whole scene now.

The scene in the pictures is quite a bit after she arrives, so it’s entirely possible we might see Jessica Gutenberg. And I think the buttoned shirt (in a pretty 20th century silhouette) is a costume design decision to show that Claire is a woman out of her time.

Love this article!!!!!

I wonder if the myth of no buttons has something to do with the myth that the Amish don’t use buttons (some do, some don’t). The “logic” being that since the Amish are all kinds of “ye olde timey” and they don’t use buttons, then buttons weren’t used in olden times.

All kinda holes in this theory of course … maybe they are buttonholes :-)

Hey Donna, yes I was thinking the same thing. Although I was wondering if it was some branch of those lovely puritan pilgrims who thought buttons were “adornment” and were so frowned upon it was as if they never existed???

As someone who studies historical passementerie buttons, Thank You! Now can you address the fact that there aren’t nearly enough deathshead buttons depicted! ;) They were so common they should be in every adaptation.

I know I’ve heard that ‘buttons were only decorative’ before ‘insert time period here’ repeated by various ppl in reenacting groups. I didn’t really understand it bec. why would you have a button & an fabric overlap & some other type of closure underneath, but not just use a simple hole for the button to go thru? That seemed to over-complicate matters. And you always want to go for the simplest method first.

Ugh. I remember reading a journal article by a fairly respected costume researcher back in the … 30s? … who was beating his breast because he’d bought in for so long to the “no buttons, or if yes, then only for decoration” argument for the 14th century, till he got up close to the weepers on Edward III’s tomb and saw not only buttons, but button HOLES on a couple of the males. But he held to his argument for women. If he had looked to the left or right a couple of feet, he’d have seen the SAME EVIDENCE on some of the female weepers … He was so proud of himself.

To be fair with the 18th century, most workday lower/poor class womens’ wear isn’t going to button. Petticoats tie, short gowns and bedgowns are usually pinned. (Note “usually.” You COULD make one that buttoned.) But that isn’t the same as NO ONE HAD EVER HEARD OF BUTTONS EVER. Men’s clothing had buttons out the wazoo and if you’re a wealthy woman or even just a reasonably comfortable one dressing for something other than workday wear..uh..why not?

Now, metal-grommeted backlacing “18th century” ballgowns….

The main reason working dress was less likely to use buttons is that working women would wear the same outfit throughout size and body changes, like pregnancy, as well as through demanding work.

Great timing! I was reading a costumer’s blog I forget where, who stated their new outfit had no buttons because period. Someone who had been costume blogging for years and really should know better.

I can’t believe this particular myth still lives. Sigh. Beautifully done rebuttal.

Bookmarking this for future use, because I know I’ll need it.

ARGH! Those myths! That is as bad as the old SCA chestnut, Pink isn’t Period before the 18th century. Are you freaking kidding me?! never mind all the historical portraits and existing clothing, you don’t think that red never faded in the sun or that no one ever reused a vat of dye and got a weaker color?

… pink isn’t period, but pale red is … :-)

the difference? not much

Oh yeah. Pink isn’t period is one of my FAVROITE myths.

Wait, pink isn’t supposedly period? Lolwut?

I’ve heard the button one, but never the pink. Why would pink not be period?

Great post! Conversation around it on Alys Mackyntoich’s stream made me comment here.

And I thought I’d heard all the stupid SCA myths! Never heard that buttons weren’t period.

Here is a photo of a plate from //Birka I//, Holder Arbman’s magisterial work on the Viking Age archaeological finds from Birka in Sweden. Although he combined photos of bells and buttons on this one page, do note the array of beautiful cast bronze buttons (functional and with shanks, no less) that were found in situ in men’s graves.

https://io.ua/13506900p

There are buttons on 13th century statues in Germand cathedrals, f.i. the statue of Herman van Meissen in Naumburg cathedral (1245-50) has a row of 6 buttons alonside a split in his surcotte. I’ve also seen a button on a closure flap of an albe of a saint dating to the 8th or 9th century.

Thanks for the great post! Speaking about myths around buttons, is it true about the idea that women’s and men’s buttons are on different sides due to the rich and fashionable ladies in the past being dressed by lady’s maids and so to make it easier for the right-handed maids the buttons were on the right (from the perspective of the maid)? Is this another myth? Surely gentlemen’s valets had the same problem? Please pass on your wisdom if you can, as I would love to know more! :)

I always figured it was to make it easier for hetero couples to un-button each other :-)

I don’t think there’s ever been any real consensus on why men button left vs women buttoning right. If you look at pre-20th c. sources, both male and female garments show both ways. My hunch is that it is something that developed with the mechanization of the fashion industry in the 20th century and may have even been an arbitrary design choice.

Thanks! Yes I wondered whether it was just an arbitrary choice that stuck… Haha Donna – that’s an idea!

Yes! Thank you! I hate it so much when people post things on the internet without doing their research first (why can you see buttonholes, if they weren’t functional buttons?!)

Can anyone help me with a vaguely related question– my previous boss (who knows a LOT about costume history) once told me that at some point in history (middle ages? unsure) buttons were considered sinful and in paintings you can see people being tortured in hell for wearing them and a bunch of other stuff and that lacings were seen as the morally upright fasteners.

Is this true?

Sounds like bladerdash and piffle to me.

Of course that should be: balderdash.

At least if you’re in Great Moravia, they’re as old as 9th century:

https://cs.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gomb%C3%ADk

Probably doesn’t apply to buttonholes, but hey, that’s a different thing! ;-)

(Sorry for the Czech, the Wiki article doesn’t come in English.)