This is a guest post by Shashwat, a part-time tailoring geek and a full-time South Asian history connoisseur. Their area of interest includes formation of post-colonial national identities out of an amorphous and volatile subcontinent, and what could be more volatile than fashion.

With the recent release of final installment of Mani Ratnam’s adaptation of Kalki’s Tamizh historical epic novel, Ponniyin Selvan, I thought it would be a good moment to revisit the 2018 Hindi film Padmaavat which was based on the eponymous 16th-century Awadhi epic poem. [Content warning: Discussion of Islamophobia, mass suicide.]

Set around the 1301 siege of Chittorgarh by Sultan Alauddin Khilji, the poem is a metaphorical Sufi meditation on temptation, reason, and sacrifice. With a narrative involving talking parrots and mystic sorcerers and gods testing the love of protagonists, the poem claims no historical authenticity. However, in the subsequent heated climate of colonial politics, the story acquired a distinct ethno-religious flavor (thanks to problematic orientalist fantasies of British military officers like James Todd) and by the 19th century, Padmaavat was reframed as a real historical event, symbolizing the moral victory of “Hindu Rajputs” over “Muslim invaders” thanks to “voluntary mass suicides” of dutiful Hindu wives (too much to unpack here, but for the moment, let’s throw the whole suitcase of propaganda away).

While Sanjay Leela Bhansali claimed his work to be based on Jayasi’s poem, the movie leaves out most of the outlandish elements of the epic and also presents a very problematic religious narrative of the events, conspicuously absent from Jayasi’s beloved work. As such, I am going to consider it as a period drama set in 1300-1301, narrating an actual historical event (the capture of Chittorgarh by Khiljis) and taking significant (-ly problematic) liberties with how it actually played out.

The plot focusses mainly on the Khilji and Rajput kingdoms with a few minutes spent on Queen Padmavati’s life in Sinhala kingdom (Sri Lanka) so let’s take a look at them one by one.

Here’s what two of the costume designers, Rimple and Harpreet Narual, said about on working on the film:

“Working on a project such as this is just not about creating stunning garments, but also depicting the director’s vision for his characters and story line as authentically as possible. The clothes have to evolve in the same way the look of every character evolves through the movie. The clothes have to be in sync with the characters’ moods as well as the overall flow of the narrative, bringing out underlying emotions as well the intricate nature of the characters and the plot, so the colour palette, fabrics, surface ornamentation all had to be worked out accordingly.

As there were no man-made fibres at that time nor was sericulture prevalent in the sub-continent, we have avoided using the silk or other Chinese substitutes and only used organic cottons and muls along with traditional decorative arts and techniques such as block printing and “varq ka kaam” that were prevalent then.”

They certainly eschewed the “modernizing history for a contemporary approach” aesthetic in favor of opulence, not unexpected for a showman like Bhansali.

Clothing in Sinhala

Our main source of information about Sinhalese fashion in early mediaeval Sri Lanka comes from frescoes in the ancient rock fortress of Sigiriya, which was functioning as a Buddhist monastery until the late 14th and possibly early 15th century.

One notices some key patterns in the clothing depicted — fabric on the lower body wrapped as a dhoti, with the torso being uncovered or clad in a very fitted blouse (kanchuka). The colors are adequately deep and vivid as one associates with south Asia and the most eye-catching part is the elaborate hair-do’s.

Compare this to the movie which, um, mehhhh:

I am not going to say anything about this Katniss Everdeen cosplay. Of course, she had to wear an obvious wig and let it down for hunting in the wild eyeroll

She next wears this milk porridge colored nightie-esque ensemble to pray to Buddha by playing with the cylinder tambourine thing (which sure looks fun, but is inaccurate). The drab color was likely an artistic liberty to contrast the simplicity of Padmavati’s Buddhist youth with the bloodbath that would follow, same for the loose hair with no attempt to recreate the complex updo’s. What I absolutely do not get is the loose full-sleeved top; it’s reasonable they couldn’t risk showing the queen in a short, fitted blouse due to orthodox views of militant censorship organizations, but they could certainly experiment with draping the shawls to achieve the same coverage.

Padmavati wears no jewelry in these scenes, barring a septum ring (which she retains even in Chittor, a nice touch of her roots).

She talks to King Ratan Singh, whom she accidentally shot while hunting, and he proposes to her in this scene with her wearing a similar outfit as in a peach shade, which is basically the same as the previous outfit but for A COMPLETELY RANDOM DIAGONAL FLORAL DETAIL ACROSS THE BODICE.

If the goal was to show simplicity, random anachronistic diagonal embroidery is the last thing to represent that with the amount of fabric rendered directionally unreusable. Also, her hair is significantly straighter (and blacker?) since her first appearance, which I will be coming to in a minute.

Clothing of the Rajput Women

Ratan marries Padmavati, takes her to Chittor, his first wife Nagmati is not pleased (which everyone ignores because this is the 1300s, and misogyny is more common than fresh drinking water), Padmavati dances, a royal priest is caught letching at her and is exiled, the priest convinces Alauddin to invade Chittor to capture the beautiful queen and what follows is war and death.

So, what did the Rajput women wear? A gathered skirt (ghagra), blouse (kanchala), and veil (odhni). This is the basic west Indian attire even today, but historically there were significant differences.

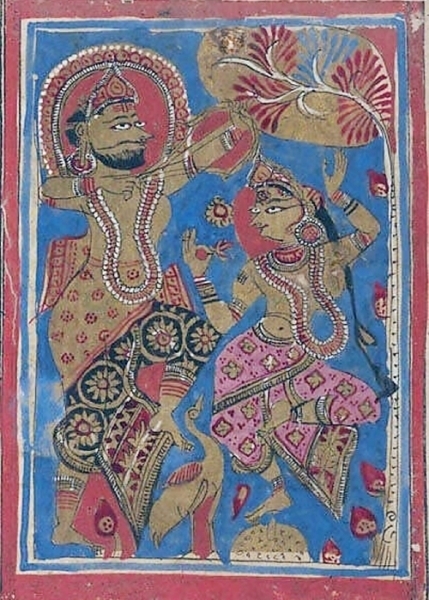

The main visual artwork from the era comes from Jain Kalpasutra manuscripts, and, with stylistic similarly observed until the 1450s in works such as Gita Govinda manuscripts. The blouse seems to go well past above and below the bosom, and the breasts appear separated but not lifted-up-to-armpits as the later Hindustani miniature paintings depict (anachronistically adorning the palace walls in the movie).

The movie seems to have the idea about coverage and bust placement, which it achieves successfully albeit with an inaccurate construction method — princess seams.

Historically post-Mughal fashions had blouses cut in the kanchli pattern. The accentuated seams give an idea of the construction

However, the earlier styles, where the movie takes place, possibly had gathered instead of shaped cups, like the rabari blouses worn by nomadic tribes in the region even today:

The belly portion is a flap and could be as short as a couple of inches; it has two pairs of ties at the back one at the nape and one at line of lower ribs.

The gathered skirt appears to be very narrow, seemingly just a simple gathered rectangle without any gores (which were a later Mughal influence). The movie goes for a gored skirt, which looks grand and imposing but is rather anachronistic.

Padmavati also randomly gets a side-tucked green panel of fabric for the dancing outfit, and it is unlike anything from the period (not even the ‘patka’ which was a later Mughal fashion worn exclusively front center).

There is thankfully not much scope to be inaccurate with veils, considering it’s a literal rectangle with ornate borders, so not much to comment.

The character of Badal’s mother was appropriately attired as a widow in similar outfit as others except in blue.

Rajput Men’s Fashion

We don’t have a lot of regional Jain representation of men in this period (most of the male figures being monks) so a good source of research can be Alchi monastery frescoes, commissioned by northern Rajputs. The predominant fashion trend seems to be draped dhotis and flared panel side-tying dresses that are similar to later angarkhas but to avoid anachronistic terminology we shall stick to calling it ‘poshak.’ The movie goes for a much fuller skirted look, the fitted bodice with gathered skirt jama, that seems to have emerged only during the 15th century and achieved the fullness as depicted in the movie not until late 16th century.

Stunning to look at, but too early by a couple hundred years.

Notice the similarity to this 17th-century piece (and we are supposed to be in 1301).

I did like how the turbans were draped with varying levels of fullness throughout the movie, adding a touch of realism since these aren’t pre-stitched garments and done anew for the occasion.

The Jewelry

Women ornamented themselves through necklaces (haars), armbands (bajubands), nose rings (nathnis), finger rings (arsis), bangles (kangans in precious metal, glass, lac, and conch, usually multiple at once), anklets (payal/pajeb/nupurs), waistbands (kamarbands), earrings (kaanbaali/jhumkas) and chokers (hansulis), none of which the movie skimps on (par de course for Bhansali, who is the epitome of Bollywood glitz). One issue I had is with the headgear; in addition to the forehead parting jewellery (borla), hairline adornment (mathapatti) and jeweled head bands with discs (rakhdi), the period paintings repeatedly show a tiara-like piece worn at the top of braid tucked in a tiny bun; this is possibly a ‘khopa’ or metal comb.

This was the only piece missing from the movie possibly because of the complexity involved in incorporating a tiny bun with a braid necessary to hold it.

One would usually not nitpick the jewelry details beyond the general shape, but with the sheer amount of it involved in this movie, it is hard to overlook.

The movie actually does a good job with achieving the chunky, aged tarnish instead of going for a sleek modern bridal aesthetic. But there was one prominent error — the meenakari miniature necklace in this outfit.

Meenakari involved gold enameling to produce complex jewelry designs, sometimes appearing as detailed as miniature paintings. This technique was not as refined until the late 16th- or early 17th century (the movie seems to looooove every cool fashion trend post-16th century at the expense of authenticity). This outfit appeared frequently in promotional material, so it was a relief that the jewelry style didn’t get used much in the movie.

The men too wear jewelry as they would have done historically, with necklaces, armbands, and turban brooches. The necklaces for the king could be a smudge more ostentatious, but I guess we have to be content with them putting jewelry on men in the first place.

Hairstyles

The women all wear simple braids, which is fine for most classes, except the royalty who should have a little bun too for the khopa. Not much to say about men’s shoulder length hair — no fancy layering or mullets to worry about with turbans being worn appropriately in every public scene.

The main issue is our leading lady’s hair itself, which starts as a curly ash blonde wig.

Then transforms into less curly, more black hair and finally into this wavy texture (is this a metaphor for the jungle huntress with Merida mane being tamed into a dutiful wife with Aurora tresses?).

And then in the holi scene you notice THE FREAKING OMBRE STREAKS.

AND THE OMBRE STREAKS BLOW INTO YOUR FACE THROUGHOUT THE LONG, DRAWN-OUT CLIMAX.

For all the hullabuloo over Padmavati’s unibrow as a nod to authenticity as she didn’t have razors, the streaks were a step too bizarre.

The Fabrics and Embellishments

Flawless, would be my description of the Rajput fabric choices for the movie. You can tell from the screen that it’s organic cotton, hand-dyed in vegetable dyes. The movie foregoes silk, which makes sense as is unsuited to hot desert climate. The result is still absolutely regal thanks to block printing and gota patti embroidery embellishments. And often they appear together, a completely period approach to ornamentation. Just gawk at this odhna.

Again mixing tie-die polka ‘bandhani’ prints with gold gota accentuation over the patterns.

Subtle stripe action with ‘leheriya’ print in grey on white.

Or this panchranga (lit. five colour dyed) wedding lehenga, dyed in chevron stripes!

The men go full floral prints.

Once again, the dancing outfit had some issues — the embroidery patterns along the hem include anachronistic 16th-century miniature inspired motifs.

The Colors

The plot narrative is very black and white — white goody good Rajputs and Evil with capital E Khiljis, hence unsurprising that the costumes depict the theme so clearly. Padmavati’s Buddhist maidenhood is highlighted through drab colours screaming asceticism.

The Rajputs wear warm, bright colors such as red, gold, orange, in contrast to the dark velvety green and blue shades of the Khiljis. The movie projects the communal animosity and Hindu nationalist aesthetic of kesariya/bhagwa (saffron orange, for Hindus) and hara (green, for Muslims) on its characters, not just through costumes but even the palace decor.

Padmavati is an interesting case because of the subtle but striking use of a pop of green and teal and in her outfits despite being on side of Rajputs.

The shade appears in her kanchalas, side skirt panels, shawls and even full attires (when meeting the priest, and again in her argument with the commander in chief; both scenes being her girl-boss moments).

While her final dress has no green, the uncut emeralds framing her face are unmistakable.

Also notable was the use of white when she shows herself in the mirror to Alauddin against the king’s fears that it would defame her character, thus the white reaffirms her “purity” (did I mention the blatant “good wives should stay at home” glorification in a movie that romanticizes coerced suicides?).

Or the very obvious religious reference by having Padmavati wear orange while saving Ratan, like Rama rescuing Sita.

The climax, with Padmavati standing out in magenta amidst a sea of red passing through the earth-colored hallways was a moment of excellence for the costume designers, cinematographers, and set artists; if only this wasn’t set to glorifying a mass suicide.

Costumes of Khiljis

For reasons pertaining to religious injunctions on prohibiting depiction of human figures in art, there is limited surviving art for inspection of fashion in the early sultanate period. However, a unique style combining Indo-Persian influences emerged in the early 15th century following patronage by Tughlaqs, which should give us an idea about the sartorial aesthetics of the previous period.

Men appear to be attired in side-tying fitted robes and loose open overcoats with different kinds of turbans and hats. The women wore multiple layers of robes. They could wear a cotton shift called gomlek, followed by a fitted jacket called yelek, followed by a visible robe called entari with an overcoat. The colors are saturated and vivid.

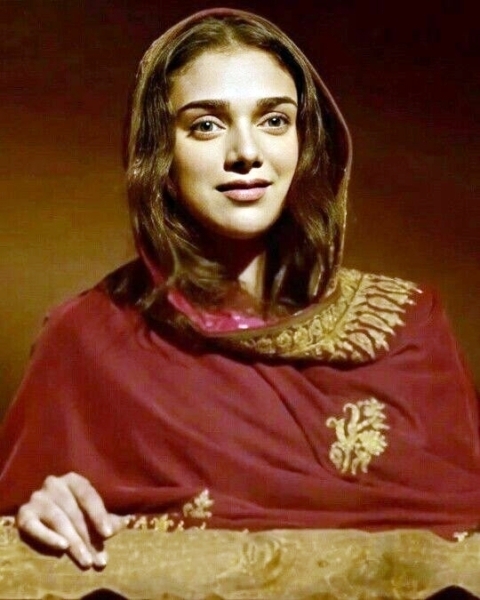

The movie checks out for the women’s costumes, significantly Alauddin’s wife Mehrunissa.

Pink entari over a dark green yelek.

Green entari over red yelek. The jewelry is to die for.

Vividly embroidered entari with a relatively plain yelek.

Drowning in red as she receives the news of her father’s murder by her husband; the braids, while not inaccurate, give a very romantic Ophelia-esque touch.

The embroidery has central Asian influences, while the vivid reds evoke south Asian association with bridal bliss appropriate for the Khiljis, who inherited a legacy of shared cultures in the amorphous landscape of mediaeval subcontinent.

She isn’t immune to lack of bobby pins though in her introduction scene:

Coming to the men, well they wear side-tying robes and ornate overcoats, but compare the manuscript images above to … this:

Khiljis washed their faces. Khiljis wore colours other than green and black. Khiljis didn’t wear fur in this tropical heat. Khiljis didn’t let their locks loose in the middle of a sandy desert when it could be tucked away neatly under a turban. Khiljis were sensible humans, you know, unlike the savage animal imagery Bhansali wanted to evoke. Authenticity was sacrificed, nay, butchered, at the altar of Islamophobia.

For Alauddin, it’s either looking like Khal Drogo, or having in his eyes the sadness of a Eastern European.

Malik Kafur, Alauddin’s confidant, commander and possibly lover (portrayed in a bizarrely queer-phobic and simultaneously sexy way by Jim-daddyyyy-Sarbh) dresses way more neatly than the king. Insert “spent too long in the closet not to have a good wardrobe” joke.

Those stripes are the straightest thing about Kafur.

My man rocks gold couched embroidery effortlessly, even as the enemy sniggers at him being the “Sultan’s begum(wife).”

To sum up, Padmaavat was an opulent feast for the eyes, and fulfilled the “creative vision” of warm noble Rajput attires and evil green Slytherin-esque Khilji robes. But the liberties taken and choices made raise an important question — when do creative liberties cease to be mere logistical choices and slip into sinister propaganda? The movie plays fast and loose with historical fashion throughout, sometimes going a solid 500 years too early; the portrayal of Khiljis however rakes the cake for the obnoxious disregard for nuance while unleashing every “savage” costuming trope on the Muslim Khiljis. And that, is where it becomes important to critically analyze the visual storytelling of period dramas.

Have you seen Padmaavat (2018)?

Never saw it. Not going to watch it. I’m South Asian myself, and if I wanted to watch cartoonishly political propaganda dressed up in anachronistic costumes aiming more at being some designer’s next wedding collection than at being a serious re-creation of a specific time and place, I’d watch Lagaan instead. Equally misogynistic story; better music. The beloved Amar Chitra Katha comic books of my youth presented this story qua story, with simpler costumes drawn to easily identify character and status. That was better.

Indian dress is very gorgeous to western eyes, not that our own medieval nobility didn’t dress pretty gorgeously too but your fabrics seem better.

Wonderful, wonderful article! So evocative and thought provoking – I can’t wait to see, simply for the opulence of it all… even though many of the themes do sound problematic.

As I understand it, in the epic the mass suicide is intended to rob Alauddin of the prize of his victory. I see the point but I admit to having problems with it. I mean Padmavati was the prize, surely her death would have been enought to achieve that?

I hope you don’t mind a question that is not about the movie. I’m looking for a good “bird’s eye” overview of the history of art of India. I’m especially interested in costume and jewelry, which most general art historians don’t give much attention to. I can read English and German. Hope you can recommend some generally available books.

Thanks for this post, this is the kind of stuff I find really interesting! (Both as a very pasty white American who likes to learn about other culture’s sartorial traditions, and as someone who works in theatrical costuming).

Would there be any chance of doing a review of “Jodhaa Akbar”? The costumes in that movie were GORGEOUS and (at least to my Western eyes) seems to be a bit less problematic on the religious propaganda front (since the whole movie is about Muslim King and his Hindu Queen getting married for political reasons but learning to love and trust each other over the course of the film). I would be curious to know how historically accurate those costumes are!

We have a general review of that one, but could always use a more nuanced review — here’s ours: https://frockflicks.com/jodhaa-akbar-2008/

Thank you so much for this post! I learned a lot and really enjoyed it. I’d love to read more posts about costuming outside of Western/Eurocentric period pieces.

So ..uh…this movie is Islamphobic? but the narrative clearly blames the start of this bloody war on a Brahmin Hindu Priest and shows the movie has good Muslim people too aka Mehrunissa?Or have the writer forgot she is Muslim too?

Even the so called glorification of suicide from what I watched is played with tragic undertone since the people dying also involved are pregnant, children, clearly in despair and put up last token of resistance. Even the whole saffron v/s Green aesthetic looks a little laughable nitpick considering the movie’s lighting for Khilji faction is mostly Gold, Black and Amber not even dark green( can be seen in screenshots put up by the writer as well)

I am thankful for details on historical accuracy and pointing the details and history but Not really impressed by the clear beef the guest writer has for ..idk..not portraying conquest and slavery as something amazing and how it is indeed verified by historians has religious fanaticism being one of the many driving reasons for it( mostly to funnel the Indian subcontinent’s riches etc)

( as it is its not even a now concept to peddle fictional and semi historical tales as “accurate” in historical fiction movies anyway. Its dumb but nearly every Historical fiction movie does it. Even Jodha Akbar despite everyone with a legit research degree saying Jodha probably never existed )

Incidents of mass suicides to avoid capture and slavery occur in many cultures and is always winceable no matter how much you understand the motivation.

I am not exactly sure how a mass suicide by citizens panicking under a brutal military attack amounts to “resistance” that the movie portrayed it as, nor do I get get how the siege of a Rajasthan fort by a Delhi Sultan was in any way related to funnelling of India’s resources(unless we are confusing Alauddin with Timur or Nadir Shah). And the “good Muslim” trope, well, that doesn’t really serve as a compliment to the movie.

Ahistoricity of the narrative isn’t the problem- check Gulzar’s ode to Meerabai- it’s the communalising of an epic love poem from a skewed perception of history that’s irksome.

So you NOW acknowledge the movie is showing some sort of panic and unsavory aspect of the mass suicide ? that was quite fast downgrade from saying it was “glorification”.

Frankly from what I saw the movie’s black and white narrative skews more towards gender than towards religion. Where every woman is saintly and men are the worst since the control everything. Including the first wife which contrary to your claim is not ignored by the narrative at all. She prominently features as a person who while existing in society which accepts polygamy for men still cannot accept it in her heart and is not villainized for it( it would be odd if she was considering Bhansali’s own mother was left by her husband cruelly for another woman once)

Frankly I would just say I am agreeing to disagreeing for I find the argument of the movie being particularly communal to be very weak. The details on history for the costumes were nice since I also found many elements to be too forward in centuries fashion wise. I guess we can chalk it as stylistic choice since Bhansali rarely works with parred down aesthetics.

Also I didn’t meant people dying en masse as resistance. More like scenes of them attacking the soldiers being one.

I enjoyed the review and the beautiful pictures for which I thank but found the article very preachy. I understand there’s extremely serious communal tensions in India right now (and not just right now) and that Hindu propaganda in art is a problem, but everything I read in English lately seems to have this exhausting virtue-signalling and one-sided “problematic this, problematic that” bent. Even, especially I would say, stuff about fashion and clothes!

Out of curiosity, I checked out the review of “The Warrior Queen of Jhansi” on this very website, having remembered something about the British being in it, and in that case, the Brits all being villains and horrible people is “fine”, they deserve it!

So which is it? Are all invaders evil, or not, depending on which group is fashionable to hate upon and which one isn’t? The Islamic invasions in India were extremely brutal.

As for mass suicides, they are very common in history (from the Jews losing to the Romans to the Japanes to the Americans), of course we don’t like it now because we’re not being attacked with nowhere to go but instead of calling it problematic I’d be interested in an interpretation of different meanings given to suicide in different cultures and the fear of enslavement/rape motivating it.

What do you mean by “having in his eyes the sadness of a Eastern European”???

I am Eastern European, actually, and I don’t understand what that phrase is referring to. Would be curious to know, though.

It was a reference to a common error(that the movie too commits with it’s costuming and architecture being all over the place) of confusing mediaeval Turks(perceived as Eastern European by many south asians), Khiljis, Mughals and colonial era Nawabs into one cohesive oriental entity spanning across time and geography, and further projecting the Nawabi stereotype of pensive love struck man on them all including the Turks. It’s like how most south asians would imagine Julius Caesar to speak in a posh British accent; a stereotype that exists as an extension by error of association.

Oh wow 😄 thanks for the info. I would have never guessed that the Eastern European means Turk here 😀 Much of what is considered “Eastern Europe” are very far away from Turkey or what ever belonged to the Ottoman Empire (eg. Poland, Belarus, Lithuania, etc) 😀

Considering that the stereotype, or “most typical”, Eastern European looks are usually blonde hair and blue eyes, and the stereotype Turk look is, well, the “opposite”, with dark hair, dark eyes, etc, this is very weird to me 😄

Yes, it’s funny that Turks are seen as Eastern European as Turks are in many ways the ultimate “other” to us, and especially to Eastern Europeans themselves!

It’s a bit different with Ukraine right now because they need to “other” Russia instead, but Turks are definitely not European to an European, rather they are stereotyped as exotic, menacing, Oriental etc.

I mean, they can be “categorized” as South European or Mediterranean, as they have some in common in “looks” and in other things with Greece, Spain, etc. But Eastern European, I would never imagine that 😀

Yes and no. The Spanish and Southern Italians have mixed with both Arabs and Germanic people, and it shows. They don’t look like Turks at all to me. Turks originally come from Central Asia, so neither Northern Europe nor the Mediterranean. Greeks look more like Turks due to the invasions and the Ottoman Empire.

Now that we’re seeing a lot of Ukrainians in the news, I see how they are closer to the “Turkish” look than, say, the Belarusian (who look Slavic and Baltic to me). Maybe because of the Tatar and Greek communities?

I thought it was just a joke about eastern European literature (particularly Russian literature) being notoriously depressing!